An Algorithmic Becoming

From music playlists to credit scores, our lives have become deeply entangled with algorithmic technologies. How do we begin to understand this ‘algorithmic becoming’?

Hey, can you play me that song with the ‘fishnet’ on it?

My friend chuckled.

We were in her car on our way back from a spot in North Bali, having spent three days there on a New Year’s trip. It was a long drive. About 3,5 hours. I had gotten familiar with the songs on her playlist during the drive up north.

How did you come across this song, I asked. TikTok, she said. She opened her Spotify and told me the ‘fishnet’ song was on this playlist. We’ll get to that song eventually. Is this whole playlist from TikTok, I asked her. Yes, she said again.

In case you’re wondering, the song I was referring to was Heidi Montag’s I’ll Do It, originally released in 2010. It was part of Montag’s debut album Superficial, which, at the time of its release, “flopped spectacularly”.

In the first week, Montag sold less than 1,000 copies—a sad 600-something count—and received scathing reviews from music critics. One review wrote: “Despite having 10 cosmetic procedures in one day to improve her look and help boost her career, Heidi Montag has failed to capitalise on her new face and body.” Another review gave the album one star, and said: “The album has no life, no emotion, no passion, and sadly, that’s not even the worst part.”

The worst part? Montag spent almost US$2 million of her own money to make the album. That, according to Montag, was every single dollar she had ever earned. She had gone broke during the making of the album, which took her three years to complete independently.

In an interview in 2010, she was asked, “What happens if you don’t earn your money back?” To which she replied, “That’s not even a possibility. I think within the first week, we will definitely make our money back. The songs will make an impact in pop history.”

Well, it did. It just needed an extra thirteen years.

The sped-up version of I’ll Do It went viral on TikTok in 2023, bringing newfound appreciation to Montag’s work. To date, her song has been used in over 87,000 TikTok videos. The TikTok virality has led to the production of a music video for the song—it never had one—which premiered on January 16, 2025.

At the time of writing, the music video has been viewed over 15 million times. The release of the music video happened in the same month Montag and her husband lost their home in the devastating Los Angeles wildfires. Support from fans and celebrities came pouring in, bringing the song to the top of multiple music charts.

I didn’t know all that when I first listened to the song in my friend’s car. I just liked it because it was catchy. Especially that ‘fishnet’ part. Stilettos and fishnets, if that’s what you like. There is something about the sound of the esses that is so satisfying to listen to.

I wonder if the algorithm understands that.

It’s contentious to conceptualise algorithms as a subject that has agency. What do you mean the algorithm understands? That it sees? That it decides?

An algorithm is a set of computational rules. It’s inanimate. The critic would point towards people’s tendency to anthropomorphise objects—to give non-human entities human-like qualities, including our human ability to experience and act upon things.

But to focus our efforts and attention on dismissing emerging frameworks that attempt to offer an understanding of how algorithms work is, I would argue, counterproductive to the goal of demystifying the technology. And demystify it we must.

But to focus our efforts and attention on dismissing emerging frameworks that attempt to offer an understanding of how algorithms work is, I would argue, counterproductive to the goal of demystifying the technology. And demystify it we must.

Algorithmic technologies—from TikTok’s For You Page (FYP) to credit scoring systems used by online lending platforms—are often seen as a black box. You can document the input and the output of the machine, but you can’t see what’s happening in the middle. This invisibility has consequences. It removes accountability.

Who is to blame if, rather than recommending Montag’s I’ll Do It, the algorithm pushes content promoting self-harm and suicide to vulnerable young users because the algorithm predicts—and accurately so—that this content would effectively drive up engagement among this specific cohort of users?

Or in another scenario: Who is to blame if someone with poor financial means is given a loan but fails to make their monthly payment, when in fact the algorithm has already flagged the borrower’s low repayment capacity and compensates for that by charging a higher interest rate?

These are ongoing debates that hinge on our ability to understand our interactions with algorithmic technologies. Having laid out these debates, I should make a point by saying that the story of algorithmic technologies is not limited to matters of accountability. But it’s important to highlight that because it gives us reasons to take this work seriously—the work of documenting how our lives have become so entangled with algorithmic technologies, and how to make sense of it all.

One thing is for certain: our algorithmic lives are evidence of a changing world that refuses to be simplified.

One thing is for certain: our algorithmic lives are evidence of a changing world that refuses to be simplified.

While some are exposed to harm through an algorithmic feed, others find support and community that they do not have access to offline. While others are trapped in cycles of indebtedness, some discover lucrative opportunities by having their professional profile boosted by the algorithm.

There is no one story about algorithmic technologies. These are multiple worlds unfolding. So, when we talk about algorithms, we must remember that they do not exist as a single, solid, stable entity.

If there is such a thing as “The Algorithm”, then the so-called algorithm with a capital A is a cultural entity. An abstraction of all the things we believe an algorithm is or should be. Much in the same way we talk about The Society or The Government, The Algorithm is no longer just a series of technical arrangements. It is culture.

For that reason, I am borrowing the anthropologist Nick Seaver’s framework that argues against the notion of algorithms being in culture. Instead, he argues for algorithms as culture. The first framework sees algorithms and culture as distinct entities—algorithms may shape culture and be shaped by it. The second framework sees algorithms as being composed of collective human practices. They are “culturally enacted by the practices people use to engage with them,” Seaver writes.

In that sense, when the algorithm becomes a throwback machine that resurfaces a 13-year-old song, it wouldn’t be an accurate read to say that the algorithm has changed people’s taste to the point of altering what once was a flop to now a global hit. Rather, it is a reflection of a changing time, a changing era.

Back then, when there were fewer discovery channels, cultural gatekeepers had more say as to who got exposure and what kind of exposure that was. Sixteen years ago, Heidi Montag’s work was overshadowed by her choice to get 10 different plastic surgeries done in one day, in what was a 10-hour operation. That was all the media talked about. Her choice brought attention to her as a celebrity, and drove discourse on the addiction to plastic surgeries, and the message her surgery is sending to young fans. Her wish to be recognised as a pop star gets sidelined in this beauty discourse.

Now, people don’t seem to care how many plastic surgeries she had. A good song to vibe to is a good song to vibe to. In a 2023 interview, Montag said, “This generation is actually kind of who it was made for.”

This idea of letting time pass and reveal different truths is something I am incredibly drawn towards. There are things you will only understand in hindsight, but the work of documenting things as they happen must still continue. It is the only way we are able to connect the dots later on.

That is the work I intend to embark on this year. I want to document this ‘algorithmic becoming’—the process of humans becoming algorithmic beings. That is, the many ways our lives have become deeply entangled with algorithmic technologies, what they reveal about us, and the frameworks we create to make meaning out of our relationship with the algorithms. Essentially, it is a coming-of-age story. We are kids of the internet, and now we are adulting with the algorithms.

We are kids of the internet, and now we are adulting with the algorithms.

This is going to be a series of inquiries. I am setting myself out on a mission to gather the building blocks to understand this ‘algorithmic becoming,’ and I’m taking you, dear readers, on a journey with me as I figure this out.

And what better way to start our inquiry than to explore our propensity to doomscroll? My thinking behind this starting point is that there is a reason why our lives have become algorithmic. And that’s because we’ve spent so much time with algorithmic technologies. Most of it, it seems, is through the act of mindless scrolling through our social media feed.

There’s a lot that has been said about ‘doomscrolling’. It’s a story about Big Tech’s creation of ‘the infinite scroll’, designed to get you hooked on your devices, placing you as if you’re a rat in a Skinner box. You are incentivised to press the levers with the hopes of getting a reward, and the only way to encourage you to keep pressing the lever is to design a reward system that activates unpredictably. That’s the science behind addictive technologies in a nutshell.

There’s also plenty of neuroscience takes on doomscrolling on the internet, discussing how our brains release dopamine when we doomscroll, and how our habituation to these tiny dopamine releases is causing us to lose motivation to engage in activities that require more commitment than merely scrolling down our feed—activities like reading a book, exercising, and whatnot.

But I’d like to formulate a different question. Not how Big Tech gets us to doomscroll or what happens to our brains when we do, but to put forward a more unassuming one: What are we actually looking for when we doomscroll?

Why is this an interesting question to ask with all that we’ve known so far about doomscrolling, you might ask?

That is for the next edition. I’ll see you then.

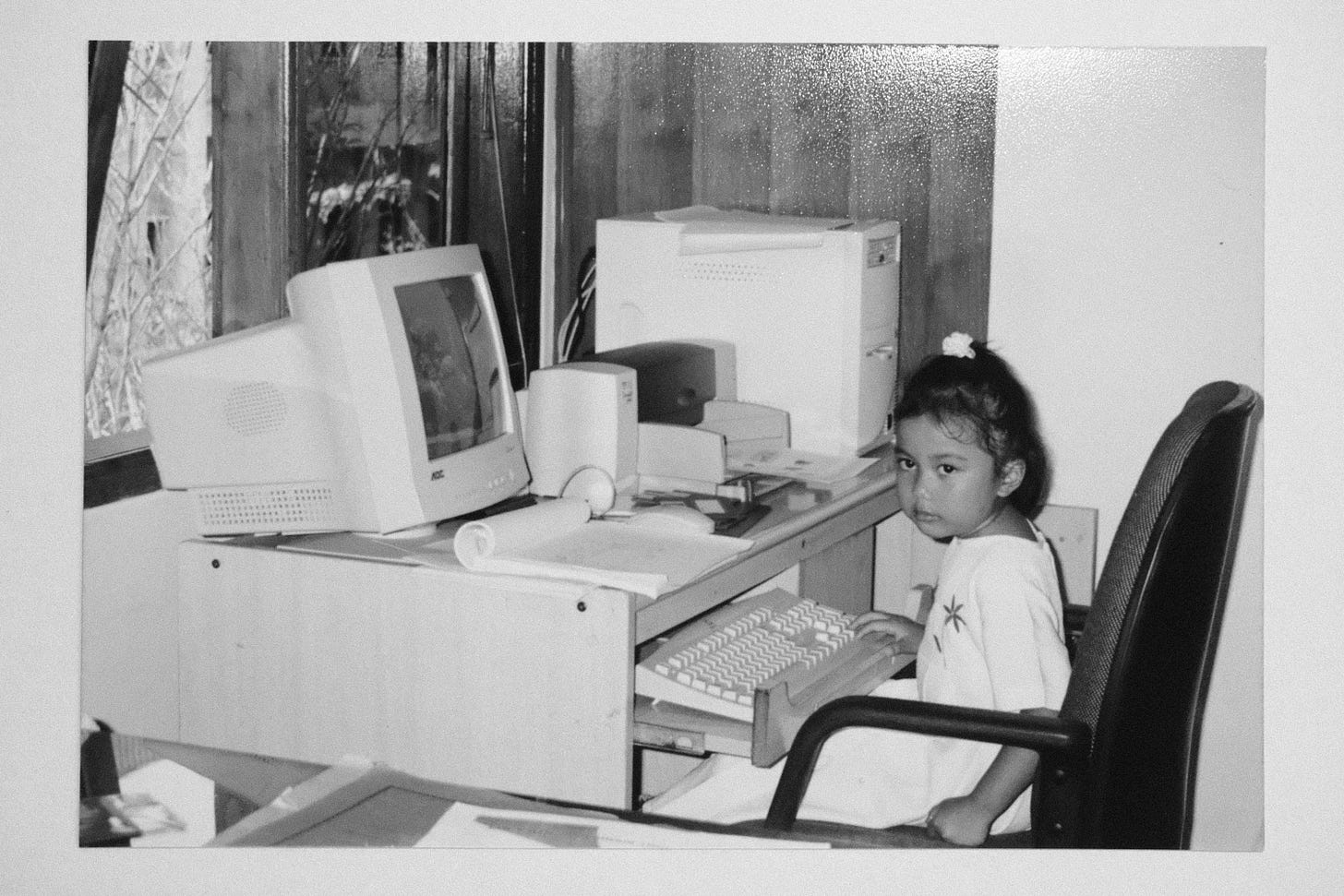

Bonus footage: Behind the scenes of recording the voice-over for this edition.